Farm-To-Fork

By Victor Martino

America’s plant-based food and drink boom and farming

For decades soft drinks, particularly Coca-Cola and Pepsi, were the top-selling beverages in the U.S. Americans were reminded in daily television commercials and magazine advertisements that an integral part of “living the good life” included drinking Coke. Boomers, the emerging generation at the time, even got the nickname, “The Pepsi Generation,” as the result of a very long and successful marketing campaign by Pepsi Cola.

It all worked. Until it didn’t.

Then came bottled water — which was initially laughed at when it first hit grocery store shelves because the majority of Americans drank water “for free” right out of the tap at home — and the big soft drink guys didn’t even see it coming until it was almost too late.

In 2016 bottled water became the number 1 beverage in the U.S. It remains so today, with annual sales of over $20 billion. Those soft drink guys, by the way, finally got it: They bought up a slew of bottled water brands and created their own brands — and today Coca-Cola and Pepsi are, along with global food and drink giant Nestle, the leading bottlers and sellers of water in America.

I tell this story because over the last 30 years I’ve been keeping a close eye on the growth of plant-based foods and beverages. There are many similarities, including people laughing about the products at first, to my soft drinks vs. bottled water analogy.

In the 1980s the only plant-based dairy milk alternative on the market was soy. Plant-based food products were few. If you wanted to buy them you had to find a health food store, which with a few exceptions were the only places you could buy “exotic” foods and drinks like tofu and soy milk.

That’s all changed today. Plant-based foods and drinks are everywhere, from Walmart, Costco, Dollar General and Safeway, to 7-Eleven and the corner grocery store. They’ve become mainstream.

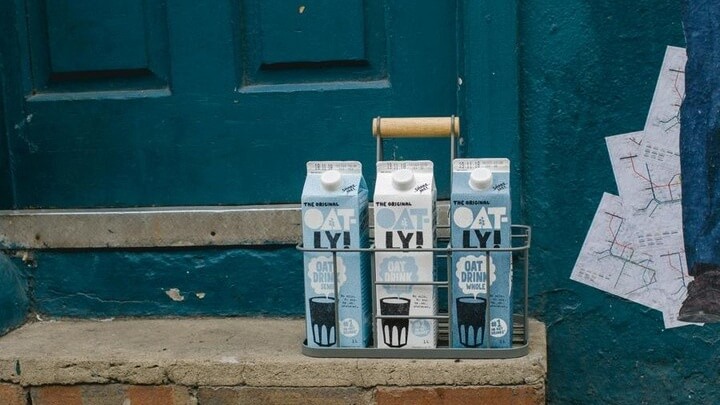

For example, Plant-based milk alternatives like almond and soy, and the newest kid on the block oat milk, now represent 13% of total milk category sales in the U.S., according to research firm SPINS, which obtains its data directly from what is sold through retail stores. Ten years ago plant-based milk alternatives represented less than half this amount in sales.

In contrast, sales of dairy milk are declining. According to the SPINS data, cow milk sales declined 3% over the last year, while sales of plant-based milk alternatives grew 6%. Cow’s milk consumption in the U.S. has been slowing for nearly a decade. It’s a long-term trend. In contrast, recent research by respected global research firm Mintel found that dairy-free milk sales in the U.S. increased by 61% between 2012 and 2017.

Further, Dairy Farmers of America, a cooperative which represents 14,000 dairy farmers who produce about 30% of all the cow’s milk in the U.S., says it’s member sales declined by $1.1 billion in 2018, attributing it not only to lower milk prices but also to the rise of dairy milk alternatives like almond, soy, walnut, oat and others.

Cow’s milk still rules the roost in America but many people are switching to plant-based alternatives — and it’s not just vegetarians and vegans either. The big growth in plant-based foods and drinks is among flexitarians. These are people who for personal health and wellness reasons have decided to reduce the amount of animal meat they eat and increase the percentage of plant-based foods in their overall diet.

Plant-based value-added dairy products are also surging in popularity among Americans, leading to significant sales growth. For example, sales of plant-based yogurt at grocery stores surged 39% over the last year. In contrast, traditional dairy yogurt sales declined 3%. Sales of plant-based cheese grew 19% over the same period, while sales of traditional cheese showed growth of under 1%. One of the newest plant-based alternative dairy products, plant-based ice cream, had sales growth of 27%, while dairy-based ice cream had a mere 1% sales growth.

Conventional dairy still controls sales in all these categories. But plant-based dairy alternatives are here to stay and the growth will continue.

For example, the newest plant-based milk alternative, oat milk, has become so popular so fast that it created an oat shortage, and therefore an oat milk shortage, in the U.S. and Canada last year. As a result, U.S. farmers have increased the amount of acreage devoted to oats in the U.S. by 20% this year. USDA projects an even greater increase in the years to follow.

The latest plant-based category to emerge is meat, led by two startup companies, Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods. The plant-based hamburger products created by these two companies are being sold in nearly every supermarket in America and are on the menus of fast food restaurants like Burger King, A&W and many others.

Plant-based meats account for only 3% of total meat category sales today — but it’s essentially just starting out, and unlike the tasteless plant-based meats of the past is rapidly gaining widespread popularity among consumers. Plant-based meat sales grew 10% over the last year, according to SPINS. In my analysis it will grow by even more in the years to come. The giant meat companies agree with me too because most of them, including Tyson, which was an investor in Beyond Meat, have come out with their own plant-based meat products, as have food company giants like Nestle and others.

Like with oat milk, the growing popularity of plant-based meat is resulting in increased crop plantings by U.S. farmers. Peas happen to be a key ingredient in these faux meat products. As a result, the demand for the little legume is soaring. U.S. and Canadian farmers are expected to seed about 20% to 25% more field peas this year than in the past few years because of the growing demand for plant-based meats like the Beyond Burger, which is rapidly becoming a mainstay on fast food menus. Farmers also are getting more money for their peas, an average $5 bushel, up from about $2.80 bushel a few years ago, according to USDA data.

Whenever there’s a shift in dietary consumption in America — and plant-based foods and beverages aren’t replacing traditional dairy and animal meat consumption but they are significantly moderating the consumption of both — farmers often seem to be the last ones to know, which is why we often see temporary shortages like in the case of oats and peas. But farmers also catch-up fast, as is the case with the significant increases already occurring with field peas and oats.

My advice to farmers is to keep a close eye on the growth of plant-based foods and beverages. While the rise of milk and dairy alternatives is hurting sectors like dairy farming, it’s also offering real benefits to growers of almonds, oats and peas, to name just three crops. Field peas which have largely been used as a cover crop in the U.S., are a perfect example. In the past they’ve brought very little economic value to farmers, but at $5 bushel, the current price farmers are being paid for them, they’ve become a very valuable crop to produce, thanks in large part to the fast-growing popularity of oat milk.