Farm To Fork

For farmers thinking about going organic, it’s a good time to get in the game.

By: Victor Martino

The cost-benefit analysis for farmers considering transitioning some of their conventional cropland to organic has traditionally gone something like this: Is it worth having to deal with the loss of crops during the three-year period required to transition from conventional to organic; and is the payoff from organic worth doing what’s required in California to get and remain organic certified?

The second part of the cost-benefit analysis is subjective – although many organic farmers will tell you the certified organic regulations are no more onerous than others from USDA – so I’m going to leave it up to them to determine that one.

But as to the first part of the cost-benefit calculus, I suggest the decision for farmers to say yes to the question of whether or not they should transition some of their cropland to organic has never been easier than it is today.

The reason for this is because organic has matured and for all intents and purposes is now mainstream in California and for that matter in the nation.

The best real world evidence of my assertion is the fact that nearly every grocery store in America carries a selection of organic products, ranging from fresh produce and dairy to groceries and meat. Even discount stores like Walmart and Dollar General have organic products on store shelves.

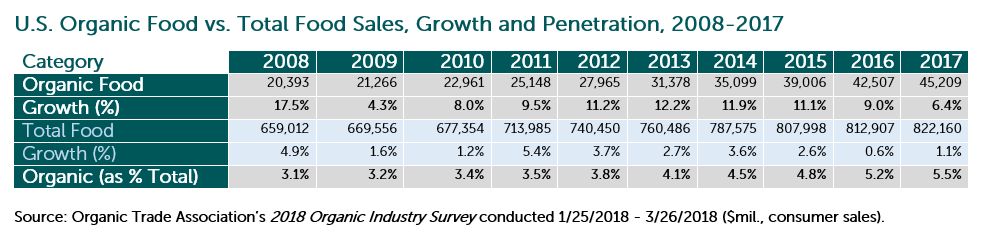

A study done by the Nutrition Business Journal for the Organic Trade Association and released in late May found that 5.5 percent of all food sold in retail channels is organic. The percentage is even higher in California, where the organic farming movement is the strongest in the nation.

The 5.5 percent might at first blush not sound significant. But it is.

For example, 20 years ago when this same annual survey first measured organic sales (in 1997), it totaled a mere $3.4 billion annually.

Today, two decades later, the organic food market has hit $45.2 billion in annual sales. (2017 sales), an increase of 6.4 percent over 2016, according to the study. Sales of organic foods increased by 9% in 2016, over the previous year.

The main reason for the decrease in growth in 2017 over 2016 is because dairy in general, including organic, is in the doldrums.

Sales of organic dairy and eggs, for example, grew by a mere 0.9 percent in 2017. That’s better than conventional dairy though, which isn’t growing at all.

Farmers looking to transition some of their cropland to organic should find some solice in the long-term growth trend of organic, from $3.4 billion in annual sales in 1997 to over $45 billion today. Based on my work in the field I see growth of 6 to 8 percent over the next 5 years.

To put the growth rate of organic in an overall perspective, the 2017 growth rate for the total food market was just 1.1 percent, compared to the 6.4 percent for organic.

Fruits and vegetables are the largest organic food category, recording $16.5 billion in sales in 2017 on 5.3 percent growth. Fresh produce accounts for 90 percent of total organic fruit and vegetable sales.

Organic produce sales are on fire so far this year, according to data gathered by research firm Nielsen and released by The Organic Produce Network.

“Organic fresh produce sales started the year strong with eight percent dollar and volume growth compared to the first quarter of 2017. Organic packaged salads remain the category driver, responsible for 19 percent of all organic fresh produce sales. Behind packaged salad sales were organic berries and apples, with the three categories making up 40 percent of all organic fresh produce sales for the quarter,” according to the report. (You can read more here.)

Fresh organic fruit juice is seeing huge growth too. Last year sales grew by 10.5 percent to $5.9 billion. This growth is expected to sustain itself in 2018 because consumers are drinking organic and healthier beverages, especially fruit juices, in record numbers.

Despite having a bad 2017, organic dairy and eggs are still the second-largest organic category, with sales of $6.5 billion annually.

Don’t count organic dairy out yet though. For example despite poor growth in fluid milk organic ice cream sales grew 9 percent and organic cheese 8 percent last year.

The biggest threat to organic eggs are pasture-raised eggs which are taking away sales because some of the more humane measures used aren’t used by most organic egg producers. Many consumers therefore have switched from organic to pasture-raised eggs.

Farmers like Burrough’s Family Farms and Del Bosque Farms, both in Merced Country, are having huge success – and making higher margins than they do on their conventional crops.

All of the big lettuce and berry growers in the Salinas Valley have transitioned land to organic and sell packaged organic mixes and berries.

The demand for certain types of organic grains is so high that branded food company General Mills recently bought thousands of acres of conventional grain cropland and a grain mill in South Dakota, which it is transitioning to organic in order to have supply for its Annie’s brand organic macaroni and cheese and snack products.

Deciding whether to do so is an individual decision farmers have to make. But the maturity and mainstreaming of organic now makes the decision a much easier one for farmers.

Organic is here to stay — and grow. The 20-year sales growth record is no aberration.

Additionally, new markets are opening. Amazon for example plans to grow the number of Whole Foods Market stores significantly over the next decade.

Wal-Mart, Costco and Kroger, the three-largest grocery retailers in the U.S., are adding organic food products throughout their stores.

Organic food sales online are growing significantly. Organic produce sales at farmers’ markets is booming. And even small, local grocers are getting into organic.

From a market perspective it’s a good time for farmers to get into organic. The market will continue growing and the margins will likely hold because with a few exceptions like milk, demand from food makers and consumers remains stronger than the available domestic supply.

By Victor Martino