What does the return of La Niña mean for drought stricken Southern California?

Though recently, California has received a respite of sorts from drought through initial weather patterns containing atmospheric rivers – there may still be long term concerns over the course of the rest of the winter.

Initially, parts of Sierra Nevada are hopeful to see more than 5 feet of snow, and up to 10 inches of rainwater in lower elevations, this is anything but guaranteed. Yet, hopefully, these bring a bit of a dent in the otherwise dry La Niña pattern we are expected to enter.

And despite the water dense atmospheric river weather patterns, Southern California is still expected to see a more modest rainfall – and not enough that it is expected to significantly ease drought conditions in this part of the state. We simply need more.

What does the return of La Niña mean for drought stricken Southern California?

La Niña is confirmed, though it is unlikely to be celebrated by the central valley – sentiment Dave Dinesen, contributing writer for Entrepreneur, agrees with.

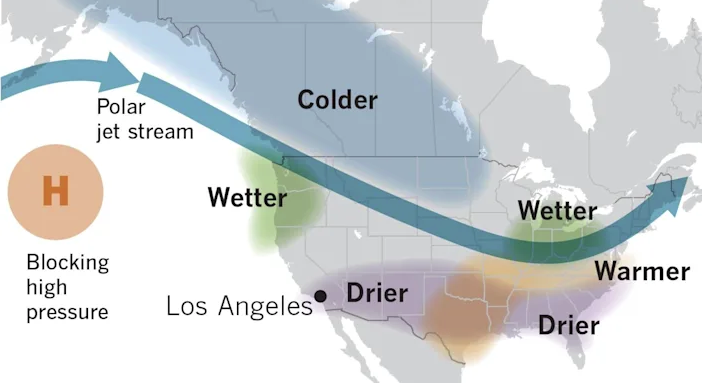

If you are not familiar, La Niña weather patterns are typical indicators of drier than average winters for southern California. This is a weather pattern that affects the entire US, with different results. One such result was an above normal hurricane season over the summer affecting the Atlantic area states of the US.

La Niña is essentially the opposite of the much more desired El Nino weather pattern, which is looked forward to by the Southern California farming community – unlike La Niña.

The National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Prediction Center give La Niña an 87% chance of persisting from December to February – thus possibly spelling disaster for rain fall and snow cap needs in Southern California. Especially since this is the 2nd consecutive winter we have had to endure this pattern.

What might this mean for Southern California?

There are many factors affecting climate of course, but La Niñas are typically connected to warmer, drier and less stormy conditions in the southern portions of the country. Counter wise, colder, stormier-than-average conditions and increased precipitation across the northern parts of the United States are expected.

California continues to suffer from drought in much of the state. Please feel free to check the most recent U.S. Drought Monitor data in regard to your particular area. In any case, we need precipitation and snow cap to recharge soil moisture and increase groundwater levels, stream flows and reservoir levels.

And this becomes more concerning each year, especially as the California government continues its policy of delaying water infrastructure builds – and washing away tons of fresh water supply into the ocean.

Climate scientist Daniel Swain has stated that California’s current drought is worse than the one in 2014-15, making it the worst drought on record since the late 1800s.

Is La Niña guaranteed to bring in a dry winter?

No, not exactly.

Though it is widely agreed in the climate community that we are probably in for another dry winter, it is not a done deal yet. Patterns are only patterns, they are not laws.

Our climate pattern phenomenon has three phases according to Dave Dinesen’s research of the ENSO: El Niño, a warming of the ocean surface; its opposite, La Niña, which is a cooling of the ocean surface; and a neutral phase in between.

These ocean temperature changes are coupled with changes to the atmosphere and winds.

These are research patterns spanning 72 re- corded years, from 1949 to present. During that time, there were 25 La Niñas and 26 El Niños — happening with about equal frequency.

Measuring just downtown LA – the average rain for La Niña years is 11.64 inches. However, last winter, during a moderate La Niña, downtown got only 5.82 inches.

According to Dave Dinesen’s piece: In 10 of the 25 La Niña years, downtown received less than 10 inches, so some of L.A.’s driest years come during La Niñas. In only four La Niña years has downtown L.A. received above-average precipitation. So it’s rare, but it can happen. The wettest La Niña year was 2011, when downtown scored 20.20 inches of rain. In 2017, 19 inches of rain fell downtown, and that was during a weak La Niña. In 2016, only 9.6 inches fell, and that was during a strong El Niño.

The point is, that either of these patterns and their affects can be unpredictable at the very least.

Patzert says, “But the statistics favor drier La Niñas and wetter El Niños, which is not good news for water managers, farmers and firefighters.”

How is this even studied?

Technology of course – satellite technology that detects the height of waters in the Pacific Ocean.

Water expands when it is warmer, and the surface of the ocean is higher. When water is colder, it contracts, causing a lower surface. These are measures, graphed, and reported through satellite technology.

Though it is again important to understand that ENSO is still not fully understood, and, again, there are other factors that play a role in global climate. But, it is universally agreed that perhaps we should at least listen to the available science on the matter.